© Шитова Л. Ф., адаптация, сокращение, словарь, 2020

© ООО «ИД «Антология», 2020

Part one

Chapter I

Scarlett O’Hara was not beautiful, but men admired her charm. In her face were the delicate features of her mother of French descent, and the heavy ones of her Irish father. But it was an attractive face, with a pointed chin. Her eyes were pale green with black lashes. Above them, her thick black brows went upward. She had magnolia-white skin – so prized by Southern women of Georgia[1].

Seated with Stuart and Brent Tarleton in the cool shade of the porch of Tara, her father’s plantation, that bright April afternoon of 1861, she made a pretty picture. Her new green dress matched the flat-heeled green slippers her father had recently brought her from Atlanta[2]. The dress showed the seventeen-inch waist, and the basque showed breasts well matured for her sixteen years.

On either side of her, the twin brothers sat in their chairs, laughing and talking. Nineteen years old, six feet two inches tall, they were as much alike as two bolls of cotton.

Their faces were typical of country people who have spent all their lives in the open and troubled their heads very little with dull things in books. Raising good cotton, riding well, shooting straight, dancing lightly, and drinking like a gentleman were the things that mattered.

Their family had more money, more horses, more slaves than anyone else in the County, but the boys had less grammar than most of their neighbors.

They had just been expelled from the University of Georgia, the fourth university that had thrown them out in two years; and their older brothers, Tom and Boyd, had come home with them, because they refused to remain at an institution where the twins were not welcome. As for Scarlett, she had not opened a book since leaving the Fayetteville Female Academy the year before.

“I know you two don’t care about being expelled, or Tom either,” she said. “But what about Boyd? He wants to get an education. He’ll never get finished at this rate.”

“It don’t matter much,” answered Brent carelessly. “We had to come home before the term was out anyway.”

“Why?”

“The war, goose! The war’s going to start any day, and you don’t suppose any of us would stay in college with a war going on, do you?”

“You know there isn’t going to be any war,” said Scarlett, bored. “It’s all just talk. Why, Ashley Wilkes and his father told Pa just last week that our commissioners in Washington would come to – to – an – agreement with Mr. Lincoln[3] about the Confederacy[4]. And anyway, the Yankees are too scared of us to fight. There won’t be any war, and I’m tired of hearing about it.”

“Not going to be any war!” cried the twins indignantly.

Scarlett made a mouth of bored impatience.

“If you say ‘war’ just once more, I’ll go in the house and shut the door. I’ve never gotten so tired of any one word in my life as ‘war,’ unless it’s ‘secession.’ Pa talks war morning, noon and night, and all the gentlemen who come to see him shout about Fort Sumter[5] and States’ Rights and Abe Lincoln and their old Troop[6] till I get so bored I could scream! And I’m mighty glad Georgia waited till after Christmas before it seceded or it would have ruined the Christmas parties, too. If you say ‘war’ again, I’ll go in the house.”

The boys apologized for boring her. Indeed, war was men’s business, not ladies’.

Then Scarlett went back with interest to their immediate situation.

“What did your mother say about you two being expelled again?”

The boys looked uncomfortable. “Well,” said Stuart, “she hasn’t had a chance to say anything yet. Tom and us left home early this morning before she got up.”

“Do you suppose she’ll hit Boyd?” Scarlett, like the rest of the County, could never get used to the way small Mrs. Tarleton bullied her grown sons and occasionally whipped them. Beatrice Tarleton was a busy woman, having on her hands not only a large cotton plantation, a hundred negroes and eight children, but the largest horse-breeding farm in the state as well. She was hot-tempered, and while no one was permitted to whip a horse or a slave, she felt that a lick now and then didn’t do the boys any harm.

“Of course she won’t hit Boyd. Ma ought to stop licking us! We’re nineteen and Tom’s twenty-one, and she acts like we’re six years old.”

“Will your mother ride her new horse to the Wilkes barbecue tomorrow?”

“She wants to, but Pa says he’s too dangerous. And, anyway, the girls won’t let her. They want to see her going to one party at least like a lady, riding in the carriage.”

“I hope it doesn’t rain tomorrow,” said Scarlett. “There’s nothing worse than a barbecue turned into an indoor picnic.”

“Oh, it’ll be clear tomorrow,” said Stuart. “Look at that sunset. I never saw one redder. You can always tell weather by sunsets.”

They looked out across the endless acres of Gerald O’Hara’s newly plowed cotton fields toward the red horizon. Spring had come early that year. Already the plowing was nearly finished and the moist hungry earth was waiting for the cotton seeds.

To the ears of the three on the porch came the sounds of negro voices, as the field hands and mules came in from the fields. Scarlett’s mother, Ellen O’Hara, went toward the smokehouse where she would ration out the food to the home-coming hands. There was the click of china and the rattle of silver as Pork, the valet-butler of Tara, laid the table for supper.

The twins realized it was time they were starting home.

“Look, Scarlett. About tomorrow,” said Brent. “You haven’t promised all dances, have you?”

“Well, I have! How did I know you all would be home?

I couldn’t risk being a wallflower just waiting on you two.”

“You a wallflower!” The boys laughed.

“Now, come on, promise us all the waltzes and the supper,” grinned Brent.

“If you’ll promise, we’ll tell you a secret,” said Stuart.

“What?” cried Scarlett, alert as a child at the word.

“Is it what we heard yesterday in Atlanta, Stu? If it is, you know we promised not to tell.”

“Well, Miss Pitty told us.”

“Miss Who?”

“You know, Ashley Wilkes’ cousin who lives in Atlanta, Miss Pittypat Hamilton – Charles and Melanie Hamilton’s aunt.”

“I do, and a sillier old lady I never met in all my life.”

“Well, when we were in Atlanta yesterday, she told us there was going to be an engagement announced tomorrow night at the Wilkes ball.”

“Oh. I know about that,” said Scarlett in disappointment. “That silly nephew of hers, Charlie Hamilton, and Honey Wilkes. Everybody’s known for years that they’d get married some time.”

“But it isn’t his engagement that’s going to be announced,” said Stuart triumphantly. “It’s Ashley’s to Charlie’s sister, Miss Melanie!”

Scarlett’s face did not change but her lips went white.

“Miss Pitty told us they hadn’t intended announcing it till next year, because Miss Melly hasn’t been very well; but with all the war talk going around, everybody in both families thought it would be better to get married soon. Now, Scarlett, we’ve told you the secret, so you’ve got to promise to eat supper with us.”

“Of course I will,” Scarlett said automatically.

“And all the waltzes?”

“All.”

“You’re sweet! I’ll bet the other boys will be hopping mad.”

They were so filled with enthusiasm by their success that some time had passed before they realized that Scarlett was having very little to say. The atmosphere had somehow changed.

Finally, the boys bowed, shook hands and told Scarlett they’d be over at the Wilkeses’ early in the morning, waiting for her. Then they mounted their horses and went down the road at a gallop, waving their hats and yelling back to her.

They rode along in silence for a while when Brent turned to Stu.

“It looked to me like she was mighty glad to see us when we came.”

“I thought so, too.”

“And then, about a half-hour ago, she got kind of quiet, like she had a headache.”

“I noticed that. Do you suppose we said something that made her mad?”

They both thought for a minute.

“I can’t think of anything. Besides, when Scarlett gets mad, everybody knows it.”

“But do you suppose,” Stu said, “that maybe Ashley hadn’t told her he was going to announce the engagement tomorrow night and she was mad at him for not telling her, an old friend, before he told everybody else?”

“Well, maybe. But Scarlett must have known he was going to marry Miss Melly sometime. The Wilkes and Hamiltons always marry their own cousins.”

“But I’m sorry she didn’t ask us to supper. I swear I don’t want to go home and listen to Ma talk about us being expelled.”

Until the previous summer, Stuart had courted India Wilkes, Ashley’s sister. Both families felt that perhaps the cool India Wilkes would have a quieting eff ect on him. But Brent had not been satisfied. He liked India but he thought her plain, and he simply could not fall in love with her himself to keep Stuart company.

Then, last summer at a political speaking in a grove of oak trees at Jonesboro, they both suddenly became aware of Scarlett O’Hara. They had known her for years, and, since their childhood, she had been a favorite playmate, for she could ride horses and climb trees almost as well as they. But now to their amazement she had become a grown-up young lady and quite the most charming one in all the world.

They noticed for the first time how her green eyes danced, how deep her dimples were when she laughed, how tiny her hands and feet and what a small waist she had. Their clever remarks sent her into merry laughter. It was a memorable day in the life of the twins. Now they were both in love with her. It was a situation which interested the neighbors and annoyed their mother, who had no liking for Scarlett.

The troop of cavalry had been organized three months before, the very day that Georgia seceded from the Union, and since then the recruits had been waiting for war. Everyone had his own idea on its name, just as everyone had ideas about the color and cut of the uniforms. But to the end of this organization they were known simply as “The Troop.”

The officers were elected by the members, for no one in the County had had any military experience except a few veterans of the Mexican and Seminole wars and, besides, the Troop would have rejected a veteran as a leader if they had not personally liked him and trusted him. Ashley Wilkes was elected captain, because he was the best rider in the County and because he had a cool head and could keep order. Abel Wynder, a small farmer, was elected a lieutenant. He was a grave giant, illiterate, kindhearted, older than the other boys. There was little snobbery in the Troop. Too many of their fathers and grandfathers had come up to wealth from the small farmer class. Moreover, Abel was the best shot in the Troop, a real sharpshooter who could pick out the eye of a squirrel at seventy-five yards, and, too, he knew all about living outdoors, building fires in the rain, tracking animals and finding water. The Troop valued real worth and moreover, because they liked him, they made him an officer.

In the beginning, the Troop had been recruited exclusively from the sons of planters, each man supplying his own horse, arms, equipment, uniform and body servant. But rich planters were few in the young county of Clayton[7], and it had been necessary to raise more recruits among the sons of small farmers, hunters, trappers, and even poor whites.

These young men were as anxious to fight the Yankees, as were their richer neighbors; but the delicate question of money arose. Few small farmers owned horses. They carried on their farm operations with mules. As for the poor whites, they considered themselves well off if they owned one mule. They lived entirely off the produce of their lands and the game in the swamp, seldom seeing five dollars in cash a year, and horses and uniforms were out of their reach. But they were as proud in their poverty as the planters were in their wealth. So, to save the feelings of all and to bring the Troop up to full strength, every large planter in the County had contributed money to completely outfit the Troop. The upshot of the matter was that every planter agreed to pay for equipping his own sons and a certain number of the others.

The Troop met twice a week in Jonesboro to drill and to pray for the war to begin. There was no need to teach any of the men to shoot. Most Southerners were born with guns in their hands, and lives spent in hunting had made marksmen of them all.

Drill always ended in the saloons of Jonesboro[8], and by nightfall there were so many fights that the officers had to try hard to avoid casualties until the Yankees could inflict them.

Chapter II

When the twins left Scarlett standing on the porch of Tara, she went back to her chair like a sleepwalker. There was pain in her face, the pain of a pampered child who has always had her own way and who now, for the first time, was in contact with the unpleasantness of life.

Ashley to marry Melanie Hamilton!

Oh, it couldn’t be true! The twins were playing one of their jokes on her. Ashley couldn’t be in love with her. Nobody could, not with a mousy little person like Melanie. Scarlett recalled with contempt Melanie’s thin childish figure, her plain heart-shaped face. And Ashley couldn’t have seen her in months. He hadn’t been in Atlanta more than twice since the house party he gave last year at Twelve Oaks. No, Ashley couldn’t be in love with Melanie, because – oh, she couldn’t be mistaken! – because he was in love with her! She, Scarlett, was the one he loved – she knew it!

Mammy emerged from the hall, a huge old woman with the small, shrewd eyes of an elephant. She was shining black, pure African, devoted to her last drop of blood to the O’Haras. She had been Ellen’s mammy and had come with her from Savannah to the up-country when she married. And her love for Scarlett and her pride in her were enormous.

“Is de gempmum gone? Huccome you din’ ast dem ter stay fer supper, Miss Scarlett? Ah done tole Poke ter lay two extry plates fer dem. Whar’s yo’ manners?”[9]

“Oh, I was so tired of hearing them talk about the war that I couldn’t have endured it through supper.”

“Ah done tole you an’ tole you ’bout gittin’ fever frum settin’ in de night air wid nuthin’ on yo’ shoulders. Come on in de house, Miss Scarlett.”

Scarlett turned away from Mammy. “No, I want to sit here and watch the sunset. It’s so pretty. You run get my shawl. Please, Mammy, and I’ll sit here till Pa comes home.”

Her father had ridden over to Twelve Oaks, the Wilkes plantation, that afternoon to buy Dilcey, the wife of his valet, Pork. Dilcey was head woman and midwife at Twelve Oaks, and, since the marriage six months ago, Pork had asked his master night and day to buy Dilcey, so the two could live on the same plantation. That afternoon, Gerald had set out to make an offer for Dilcey.

Surely, thought Scarlett, Pa will know whether this awful story is true. It was past time for him to come home. Every moment she expected to hear the pounding of his horse’s hooves and see him come up the hill at his usual breakneck speed. But the minutes slipped by and Gerald did not come. She looked down the road for him, the pain in her heart starting up again.

“Oh, it can’t be true!” she thought. “Why doesn’t he come?”

Her eyes followed the winding road. In her thought she went to Twelve Oaks and saw the beautiful white-columned house on the hill where Ashley lived.

“Oh, Ashley! Ashley!” she thought, and her heart beat faster.

It seemed strange now that when she was growing up Ashley had never seemed so very attractive to her. But since that day two years ago when Ashley, back home from his three years’ Grand Tour in Europe, had called to pay his respects, she had loved him. It was as simple as that.

She had been on the front porch when he had ridden up. Even now, she could recall each detail of his dress. He had alighted and stood looking up at her. And he said, “So you’ve grown up, Scarlett.” And, coming lightly up the steps, he had kissed her hand. And his voice! She would never forget the leap of her heart as she heard it.

She had wanted him, in that first instant, wanted him as simply as she wanted food to eat, horses to ride and a soft bed on which to lay herself.

For two years he had accompanied her about the County, to balls, fish fries and picnics, never the week went by that Ashley did not come calling at Tara.

True, he never made love to her, nor did his eyes ever glow with that hot light Scarlett knew so well in other men. And yet – and yet – she knew he loved her. She could not be mistaken about it. Instinct stronger than reason told her that he loved her. Why did he not tell her so? That she could not understand. But there were so many things about him that she did not understand.

He was courteous always, but remote. No one could ever tell what he was thinking about. He was proficient in hunting, gambling, dancing and politics, and was the best rider of all; but these pleasant activities were not the end and aim of life to him. And he stood alone in his interest in books and music and his fondness for writing poetry.

Oh, why was he so handsomely blond, so maddeningly boring with his talk about Europe and books and music and poetry and things that interested her not at all – and yet so desirable? Night after night, she comforted herself with the thought that the next time he saw her he certainly would propose. But the next time came and went, and the result was nothing.

For Ashley used his leisure for thinking. He moved in an inner world that was more beautiful than Georgia and came back to reality with reluctance.

But the things about him which she could not understand only made her love him more. And now, like a thunderclap, had come this horrible news. Ashley to marry Melanie! It couldn’t be true!

Why, only last week, when they were riding home from Fairhill, he had said: “Scarlett, I have something so important to tell you that I hardly know how to say it.”

She had cast down her eyes, her heart beating with wild pleasure, thinking the happy moment had come. Then he had said: “Not now! We’re nearly home and there isn’t time. Oh, Scarlett, what a coward I am!”

Scarlett, sitting on the stump, thought of those words which had made her so happy, and suddenly they took on a hideous meaning. Suppose it was the news of his engagement he had intended to tell her!

Oh, if Pa would only come home!

The sun was now below the horizon and the sky above turned slowly from azure to the blue-green. Sunset and spring and new greenery were no miracle to Scarlett. Their beauty she accepted as casually as the air she breathed and the water she drank, for she had never seen beauty in anything but women’s faces, horses, silk dresses and other things. Yet she loved this land so much, without even knowing, loved it as she loved her mother’s face under the lamp at prayer time.

Still there was no sign of Gerald on the quiet winding road. But finally, she heard a pounding of hooves at the bottom of the pasture hill and saw the horses and cows scatter in fright. Gerald O’Hara was coming home across country and at top speed.

She watched him with pride, for Gerald was an excellent horseman.

“I wonder why he always wants to jump fences when he’s had a few drinks,” she thought. “And after that fall here last year when he broke his knee and promised Mother on oath he’d never jump again.”

He dismounted with difficulty, because his knee was stiff. “Well, Missy,” he said, pinching her cheek, “so, you’ve been spying on me and, like your sister Suellen last week, you’ll be telling your mother on me?”

His breath in her face was strong with Bourbon whisky. Accompanying him also were the smells of chewing tobacco, leather and horses – a combination of odors that she always associated with her father and instinctively liked in other men.

“No, Pa, I’m no tattletale like Suellen,” she assured him.

Gerald was a small man, little more than five feet tall. His thickset torso was supported by short sturdy legs. Most small people who take themselves seriously are a little ridiculous but no one would ever think of Gerald O’Hara as a ridiculous little figure.

He was sixty years old and his curly hair was silver-white, but his shrewd face was unlined and his little blue eyes were young. He had a typical Irish face of the homeland he had left so long ago – round, high colored, short nosed, wide mouthed and belligerent.

But inside, Gerald O’Hara had the tenderest of hearts. He could not bear to see a slave feeling hurt when told off, or hear a kitten mewing or a child crying; but he had a horror of having this weakness discovered. It had never occurred to him that only one voice was obeyed on the plantation – the soft voice of his wife Ellen. It was a secret he would never learn, for everyone was in a conspiracy to keep him believing that his word was law.

Scarlett was his oldest child and more like her father than her sisters Carreen and Suellen. She looked at her father in the fading light, and she found it comforting to be in his presence.

“You look very presentable now.” She slipped her arm through his and said: “I was waiting for you. I didn’t know you would be so late. I just wondered if you had bought Dilcey.”

“Bought her and her little wench, Prissy, and the price has ruined me. John Wilkes was giving them away, but I made him take three thousand for the two of them.”

“In the name of Heaven, Pa, three thousand! And you didn’t need to buy Prissy! She’s a sly, stupid creature. And the only reason you bought her was because Dilcey asked you to buy her.”

“Well, what if I did? Was there any use buying Dilcey if she was going to mope about the child? Well, come on, Puss, let’s go in to supper.”

But Scarlett was wondering how to bring up the subject of Ashley without showing her motive. This was difficult. “How are they all over at Twelve Oaks? Did they say anything about the barbecue tomorrow?”

“Now that I think of it they did. Miss – what’s-her- name – the sweet little thing who was here last year, you know, Ashley’s cousin – oh, yes, Miss Melanie Hamilton, that’s the name – she and her brother Charles have already come from Atlanta and —”

Scarlett’s heart sank at the news. She had hoped against hope that something would keep Melanie Hamilton in Atlanta.

“Was Ashley there, too?”

“He was.” Gerald let go of his daughter’s arm and turned looking into her face. “And if that’s why you came out here to wait for me, why didn’t you say so without beating around the bush[10]?”

Scarlett could think of nothing to say, and she felt her face growing red.

“He was there and he asked most kindly after you, as did his sisters, and said they hoped nothing would keep you from the barbecue tomorrow. And now, daughter, what’s all this about you and Ashley?”

“There is nothing,” she said shortly. “Let’s go in, Pa.”

“But now I’m going to stand till I’m understanding you. Has he been flirting with you? Has he asked to marry you?”

“No,” she said shortly.

“Nor will he,” said Gerald. “Hold your tongue, Miss! I had it from John Wilkes this afternoon in the strictest confidence that Ashley’s to marry Miss Melanie. It’s to be announced tomorrow.”

Scarlett’s hand fell from his arm. So it was true! She felt a sharp pain in her heart.

“Is it a spectacle you’ve been making of yourself – of all of us? Have you been running after a man who’s not in love with you, when you could have any of the bucks in the County?”

“I haven’t been running after him. It – it just surprised me.”

“It’s lying you are!” said Gerald, and then, peering at her face, he added kindly: “I’m sorry, daughter. But after all, you are nothing but a child and there’s lots of other beaux.”

“Mother was only fifteen when she married you, and I’m sixteen,” said Scarlett.

“Your mother was different,” said Gerald. “She was never flighty like you. Now come, daughter, cheer up, and I’ll take you to Charleston[11] next week to visit your aunt and you’ll be forgetting about Ashley in a week. Besides, if you had any sense you’d have married Stuart or Brent Tarleton long ago. Then the plantations will run together and Jim Tarleton and I will build you a fine house and —”

“Will you stop treating me like a child!” cried Scarlett. “I don’t want to go to Charleston or have a house or marry the twins. I only want —” She caught herself but not in time.

Gerald’s voice was strangely quiet and he spoke slowly.

“It’s only Ashley you’re wanting, and you’ll not be having him. And if he wanted to marry you, ’twould be with misgivings that I’d say Yes, for all the fine friendship that’s between me and John Wilkes.” And, seeing her startled look, he continued: “I want my girl to be happy and you wouldn’t be happy with him.”

“Oh, I would! I would!”

“That you would not, daughter. Only when like marries like can there be any happiness.”

“Our people and the Wilkes are different,” he went on slowly, fumbling for words. “They are queer folk, and it’s best that they marry their cousins and keep their queerness to themselves.”

“Why, Pa, Ashley is not —”

“I said nothing against the lad, for I like him. And when I say queer, it’s not crazy I’m meaning. But it’s neither heads nor tails I can make of most he says[12]. Now, Puss, tell me true, do you understand his folderol[13] about books and poetry and music and oil paintings and such foolishness?”

“Oh, Pa,” cried Scarlett impatiently, “if I married him, I’d change all that!”

“No wife has ever changed a husband, and don’t you be forgetting that. And as for changing a Wilkes, daughter! Look at the way they go to New York and Boston to hear operas and see oil paintings. And ordering French and German books from the Yankees! And there they sit reading and dreaming the dear God knows what, when they’d be better spending their time hunting and playing poker as proper men should.”

“There’s nobody in the County who sits a horse better than Ashley. And as for poker, didn’t Ashley take two hundred dollars away from you just last week in Jonesboro?”

“Yes, he can do all those things, but his heart’s not in it. That’s why I say he’s queer.”

Scarlett was silent and her heart sank, for she knew Gerald was right.

Gerald patted her arm and said: “There now, Scarlett! You admit ’tis true. And when I’m gone – darlin’, listen to me! I’ll leave Tara to you —”

“I don’t want Tara or any old plantation. Plantations don’t mean anything when —”

She was going to say “when you haven’t the man you want,” but Gerald got furious.

“Do you stand there, Scarlett O’Hara, and tell me that Tara – that land – doesn’t mean anything?”

Scarlett nodded obstinately. “Land is the only thing in the world,” he shouted, “worth working for, worth fighting for – worth dying for.”

“Oh, Pa,” she said, “you talk like an Irishman!”

“Have I ever been ashamed of it? No, ’tis proud I am. And don’t be forgetting that you are half Irish, Miss! And to anyone with a drop of Irish blood in them the land they live on is like their mother. ’Tis ashamed of you I am this minute.”

Gerald had begun to work himself up into a rage when something in Scarlett’s face stopped him.

“But there, you’re young. ’Twill come to you, this love of land, if you’re Irish. You’re just a child and bothered about your beaux. When you’re older, you’ll be seeing how ’tis…”

By this time, Gerald was tired of the conversation and annoyed that the problem should be upon his shoulders.

“Now, Miss. It doesn’t matter who you marry, as long as he thinks like you and is a gentleman and a Southerner. For a woman, love comes after marriage.”

“Oh, Pa, that’s such an Old Country notion!”

“And a good notion it is! All this American business of marrying for love, like servants, like Yankees! The best marriages are when the parents choose for the girl. For how can a silly piece like yourself tell a good man from a scoundrel?”

Gerald looked at her bowed head.

“It’s not crying you are?” he questioned, trying to turn her face upward.

“No,” she cried, jerking away.

“It’s lying you are, and I’m proud of it. And I want to see pride in you tomorrow at the barbecue.”

Gerald took her arm and passed it through his.

“We’ll be going in to supper now, and all this is between us. I’ll not be worrying your mother with this – nor do you do it either. Blow your nose, daughter.”

They started up the dark drive arm in arm, the horse following slowly. Near the house, Scarlett saw her mother and behind her was Mammy, holding in her hand the black leather bag in which Ellen O’Hara always carried the bandages and medicines she used in doctoring the slaves.

“Mr. O’Hara,” called Ellen as she saw the two coming up the driveway – Ellen belonged to a generation that was formal even after seventeen years of marriage – “Mr. O’Hara, there is illness at the Slattery house. Emmie’s baby has been born and is dying and must be baptized. I am going there with Mammy to see what I can do.”

“In the name of God!” said Gerald. “Why should those white trash take you away just at your supper hour and just when I’m wanting to tell you about the war talk that’s going on in Atlanta! Go, Mrs. O’Hara. You’d not rest easy on your pillow the night if there was trouble and you not there to help.”

“Take my place at the table, dear,” said Ellen, patting Scarlett’s cheek softly.

Gerald helped his wife into the carriage and gave orders to the coachman to drive carefully.

Then, smiling, in anticipation of one of his practical jokes: “Come daughter, let’s go tell Pork that instead of buying Dilcey, I’ve sold him to John Wilkes.”

He had already forgotten Scarlett’s heartbreak. Scarlett slowly climbed the steps after him, her feet leaden. She thought that, after all, a mating between herself and Ashley could be no queerer than that of her father and Ellen Robillard O’Hara. As always, she wondered how her loud, insensitive father had managed to marry a woman like her mother, for never were two people more different.

- The Great Gatsby. Адаптированная книга для чтения на английском языке. Уровень B1

- The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Selected Tales of the Jazz Age Сollection. Адаптированная книга для чтения на английском языке. Уровень B1

- The Color out of Space and Other Mystery Stories / «Цвет из иных миров» и другие мистические истории

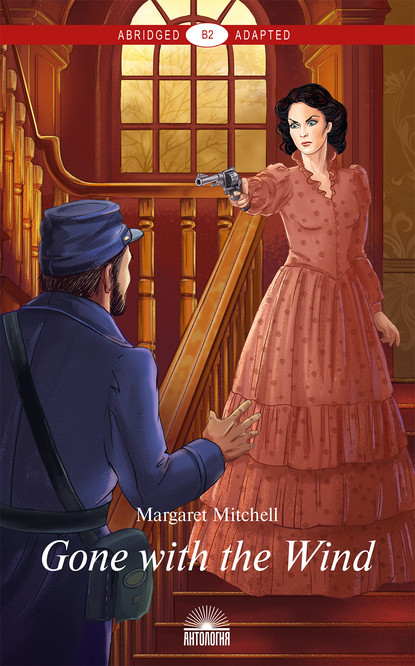

- Gone with the Wind / Унесённые ветром